I love when people remind me that it is not always the things we do that matter, but the way we do them. So much of our lives are consumed with what we have to get done that we get little time to reflect on how we are doing it. Yet it is the manner in which we do things that often makes the difference between success and failure.

A business development executive recently contacted me for coaching. Her goal? To move up to the next level. She was successful in her current role and had just received great feedback on a 360° assessment. She was at a loss as to why she was not getting the promotion she felt she deserved. When asked about her biggest challenge, she laughed and said, “richly scheduled.” I wondered what this even meant, let alone how it was getting in the way of her advancing her career. It turned out that her days were filled with meetings.

Everyone in the company complained about so many meetings, “Are you kidding? Another *@%*g meeting!” But for better or worse, meetings were part of her company’s culture and how it communicated.

Coaching allowed her to actively choose to look at things positively, whether it was meetings, work problems, or her boss! Specifically, she came to see meetings as an opportunity to share ideas, promote her team, or help others in the organization. She learned that the attitude she brought to a situation could influence others positively, which in turn made it more likely that a good outcome would be achieved. And with success, it was easier to continue to think positively, thus creating a virtuous cycle.

Another coaching client was also successful in his job. He described himself as driving results for his team. He set high standards for himself and for others. He had the respect of his team, because they knew he would roll up his sleeves in a crisis. However, he had got feedback that he was volatile, often allowing his frustration with situations and people to show. He also had a tendency to take over tasks which he saw as not being handled well by his staff. He too wanted to get promoted. But he refused to see that his behaviour was negatively impacting others. “They know how I am,” he said. And he did not understand that he needed to change these behaviours if he wanted to move up through the organisation.

The difference between the two is in their Emotional Intelligence (EQ). It is our Emotional Intelligence that underpins how we operate at work and in life in general.

So what is EQ exactly?

When Daniel Goleman first published his book on EQ in 1995, it provided the missing piece to an intriguing puzzle: people with average IQs outperform those with the high IQs 70% of the time. This finding had thrown a massive wrench into what many people had always assumed was the sole source of success—IQ (General Intelligence).

It has now been established, by Goleman and others, that EQ accounts for 58% of performance in all types of jobs. Their research has shown that a high EQ is the critical factor that separates the exceptional performer from everyone else. This is the number one reason why you should invest in your EQ. And reason number 2? Unlike IQ, which stays the same throughout our adult lives, EQ can be developed.

Emotional Intelligence is our ability to recognise and understand emotions in ourselves and others and the ability to use this awareness to manage our behaviour and relationships.

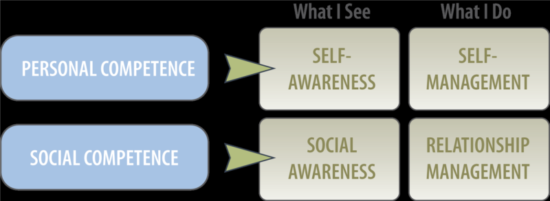

In their excellent book, Emotional Intelligence 2.0 (2009), Travis Bradberry & Jean Greaves define Emotional Intelligence as being made up of four core skills that pair up under what they call personal and social competence.

EQ is Made up of Four Core Skills

Personal competence focuses on us as individuals. It is our ability to be aware of our emotions and manage our tendencies and behavior.

- Self-Awareness is our ability to accurately perceive our emotions and stay aware of them as they happen.

- Self-Management is our ability to use awareness of our emotions to stay flexible and positively direct our behaviour.

Social competence is our ability to understand other people’s moods, behaviour, and motives in order to improve the quality of our relationships.

- Social Awareness is our ability to accurately pick up on emotions in other people and understand what is really going on – to hear the music behind the words.

- Relationship Management is our ability to use awareness of our emotions and others’ to manage our relationships successfully.

What are the benefits of developing our EQ?

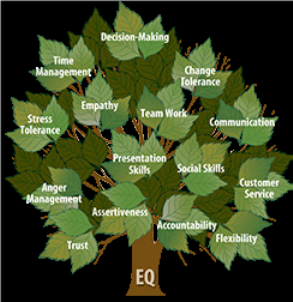

Emotional Intelligence enables leaders to identify and manage emotions in themselves and others for the benefit of their team, their customers and their organization. But EQ also underpins a host of other skills which are important for success at work.

A Little Effort Grows a Lot!

So, if we develop our EQ, we will also get better at managing stress, influencing others, communicating and making effective decisions. In a nutshell, developing our Emotional Intelligence makes us more responsive, flexible and effective leaders – reason number three.

Studies by TalentSmart, a leading provider of Emotional Intelligence products and services, suggest that 90% of high performers are also high in EQ. At the other end of the performance spectrum, only 20% of poor performers are high in EQ.

People who work at developing their EQ tend to be more successful in their jobs, because the two go hand in hand. With more success comes more money. The link between EQ and earnings is so direct that every point increase in EQ adds $1300 to annual salary. These findings hold true for people working in all industries at all levels in every region of the world. (Bradberry & Greaves 2009)

- 515 senior executives analyzed by the search firm Egon Zehnder International, found that those who were primarily strong in Emotional Intelligence were more likely to succeed than those who were strongest in either relevant previous experience or IQ. The study included executives in Latin America, Germany, and Japan. The results were almost identical in all three cultures.

- 358 managers in Johnson & Johnson’s Consumer & Personal Care Group were rated on a leadership 360° assessment. High performing managers had significantly more ‘emotional competence’ than other managers (Cavallo & Brienza 2002)

- In a large beverage firm, using standard methods to hire division presidents resulted in 50% leaving within two years, mostly because of poor performance. When the company started selecting based on emotional competencies such as initiative, self-confidence, and leadership, only 6% left in two years. Furthermore, the executives selected based on emotional competence were far more likely to perform in the top third based on salary bonuses for performance of the divisions they led: 87% were in the top third. In addition, division leaders with these competencies outperformed their targets by 15 to 20 percent. Those who lacked them under-performed by almost 20% (McClelland, 1999).

- Research by the Center for Creative Leadership in San Diego has found that the primary causes of derailment in executives involve deficits in emotional competence. The three primary ones are difficulty in handling change, not being able to work well in a team, and poor interpersonal relations.

And my ‘richly scheduled’ client?

She is now one of the top 10 business development people in the same multi-billion dollar business and has started coaching younger business development staff.

References

Bradberry, T & Greaves, J. “Emotional Intelligence 2.0.” San Diego, TalentSmart (2009)

Cavallo, K. & Brienza, D. “Emotional Competence and Leadership Excellence at Johnson &

Johnson: The Emotional Intelligence Leadership Study.” Website: http://www.eiconsortium.org (2002)

Cerniss, C. “The Business Case for Emotional Intelligence.” Prepared for the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations, Rutgers University (1999)

Goleman, D. “Emotional Intelligence.” New York, Bantam (1995)

Hunter, J. E., & Hunter, R. F. “Validity and Utility of Alternative Predictors of Job Performance.” Psychological Bulletin, 76(1), 72-93 (1984)

McClelland, D. C. “Identifying competencies with behavioral-event interviews.” Psychological Science, 9(5), 331-339 (1999)